"Saber Tooth" an extinct animal in the world

Sunday, June 20, 2010

Etymology

Anatomy

The species of Smilodon were among the largest felids ever to live; the heaviest specimens of the massively built carnivore S. populator may have exceeded 500 kg (1,100 lb).

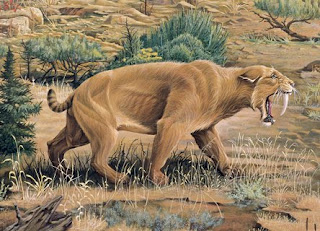

A fully-grown Smilodon weighed approximately 55 to 500 kg (120 to 1,100 lb), depending on species. It had a short tail, powerful legs, muscular neck and long canines. Smilodon was more robustly built than any modern cat, comparable to a bear. The lumbar region of the back was proportionally short, and the lower limbs were shortened relative to the upper limbs in comparison with modern pantherine cats, suggesting that Smilodon was not a very fast runner.

The largest species, the South American S. populator, had higher shoulders than hips and a back that sloped downwards, superficially recalling the shape of a hyaena, in contrast to the level-backed appearance of S. fatalis, which was more like that of modern cats. However, while its front limbs were relatively long, their proportions were extremely robust and the forearm was shorter relative to the upper arm bone than in modern big cats, and proportionally even shorter than in S. fatalis. This indicates that these front limbs were designed for power rather than fast running, and S. populator would have had immense strength in its forequarters.

Classification and species

The genus Smilodon was described by the Danish naturalist and palaeontologist Peter Wilhelm Lund in 1841. He found the fossils of Smilodon populator in caves near the small town of Lagoa Santa, in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

A number of Smilodon species have been described, but today usually only three are recognized.

- Smilodon gracilis, 2.5 million-500,000 years ago; the smallest and earliest species (estimated to have been only 55 to 100 kg (120 to 220 lb) was the successor of Megantereon in North America, from which it probably evolved. The other Smilodon species probably derived from this species.

- Smilodon fatalis, 1.6 million-10,000 years ago, replaced Smilodon gracilis in North America and western South America. In size it was between Smilodon gracilis and Smilodon populator, and about the same as the largest surviving cat, the Siberian Tiger. This species was about 1m high at the shoulder and is estimated to have ranged from 160 to 280 kg (350 to 620 lb).[3] Sometimes two additional species are recognized, Smilodon californicus and Smilodon floridanus, but usually they are considered to be subspecies of Smilodon fatalis.

- Smilodon populator , 1 million-10,000 years ago; occurred in the eastern parts of South America and was the largest species of all machairodonts. It was more than 1.22 m (48 in) high at the shoulder, 2.6 m (100 in) long on average and had a 30 cm (12 in) tail. With an estimated weight of 360 to 470 kg, and exceptionally large individuals estimated to have exceeded 500 kg[4], it was among the heaviest known felids.[3] Its upper canines reached 30 cm (12 in) and protruded up to 17 cm (6.7 in) out of the upper jaw.

Social behavior of smilodom

The social pattern of this cat is unknown. It has been suggested, based on the abundance of S. fatalis fossils in proportion to prey animals trapped in the La Brea tar-pits,[7] that they were packs of scavengers, lured in by the distress calls of trapped prey. This possibility was tested in 2008 by Chris Carbone (of the Zoological Society of London), who documented the responses of African predators of the Serengeti and Kruger National Park to recorded distress calls of prey species; it was determined that playbacks of prey sounds attract social carnivores, but not solitary hunters.[8] Additionally, some fossils show healed injuries or diseases that would have crippled the animal. Some palaeontologists see this as evidence that saber-toothed cats were social animals, living and hunting in packs that provided food for old and sick members. Living in groups might also allow more effective competition with social lions and wolves. The canine teeth and body size of Smilodon were about the same in both male and female cats. This suggests that one theory about their teeth – that they were used by males to attract mates – is incorrect.

Limbs

Smilodon had relatively shorter and more massive limbs than other felines. It had well developed flexors and extensors in its forepaws, which enabled it to pull down large prey. The back limbs had powerfully built adductor muscles which might have helped the cat's stability when wrestling with prey. Like most cats, its claws were retractable.